Of course the teens aren’t alright!

Don’t sound so shocked

I don’t know why everyone is so shocked.

Wars. Climate change. Racism. Gun violence. Book banning. Sexual harassment.

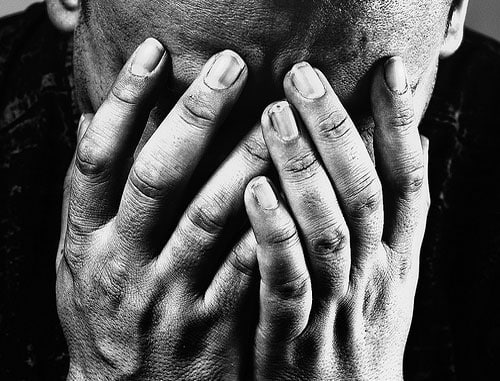

No, the teens are not alright!

Yet the headlines are met with shock — shock! — that the girls are experiencing depression and considering suicide and the boys are angry and agressive and the LGBTQ+ teens are feeling everything.

In fact, the headlines themselves sound full of dismay. “We should be alarmed,” says an opinion piece in The Globe.

First, sure, let’s be alarmed, but also recognize that while the data — the most complete the CDC has collected since the first time it conducted the High School Youth Risk Behavior Survey since it was first attempted in 1991 when participation was, to put it kindly, scant — is simply revealing hard truths.

Second, let’s also admit that many of us dealt with some of the same things in high school.

I, a GenXer, happen to remember a little band from Athens, Georgia, named R.E.M. who wrote a song that described exactly how I felt. “It’s the end of the world as we know it, and I feel fine!” I’d yell along to the chorus as I’d play the song in my room at top volume back then.

So, if you’re an adult reading this, try to remember what it was like way back when.

But this? This is not for you, dear adult. This is for the teens.

This is to tell you teens that I understand. To tell you that we, the adults, for as shocked — shocked! — as we act right now, know how shitty junior high and high school can be because we were there. And we didn’t fix it. Some things we’ve just let go. In many ways, we made it worse.

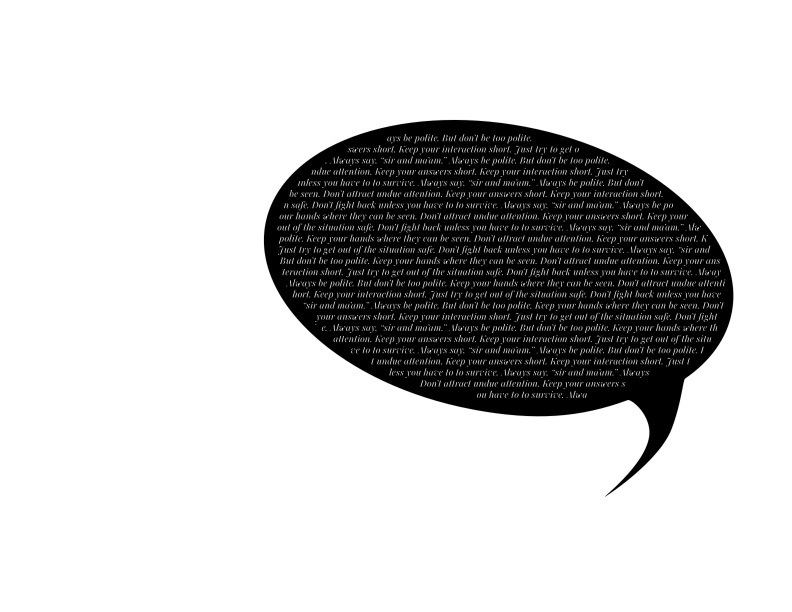

That sexual harassment and abuse girls experience? Not new. In a Washington Post piece, one teen girl described being sexually assaulted by a boy in her high school — in the hallway in sight of a teacher. The boy went unpunished. I cannot count the number of women I know with stories that range from comments about their breasts (or their lack of) from junior high and high school to bra snapping to being pushed against a locker and touched inappropriately. I know too many women who were raped in junior high and high school by a “friend” at a party. Of course, we didn’t know what to call it, so we didn’t call it rape. And other than telling each other, we didn’t tell an adult because at least one of us at some point had told a teacher or principal when someone was touched inappropriately or raped at school. The result was always the same: “Did you ask for it? What were you doing to lead him on? Boys will be boys.”

And you ask why girls are depressed, cutting and suicidal? Do you adults who find this shocking really think this wasn’t happening when we were teens?

Then there’s the boys, whose hormones are surging, but are not learning constructive ways to let out that energy. Oh, and don’t forget the media — in our day it was magazines; today it’s streaming on YouTube and TikTok and Twitch — to make sure they have all the machismo of a man. Many of them have no idea how to handle their feelings or energy, except maybe sports. And we encourage them to be competitive. We encourage them when they win. We admonish them when they fail. And we fill their heads with aggressive messages.

And you ask why boys are angry, aggressive and the most likely to commit acts of violence? Do you adults who find this shocking really think this wasn’t happening when we were teens?

What may be new to many adults is the visibility of LGBTQ+ youth. When I was a teen, I had friends my age who were open about their gender identity and sexuality with me. But they were not “out” in general. And I can tell you how much they struggled overall. Now, adults are fight over hard-won gains for the LGBTQ+ community. They are banning books in school that allow you, LGBTQ+ teens, to feel seen and heard. No wonder you feel like the earth will split open and swallow you.

And you, adults, wonder why LGBTQ+ teens have the highest rates of depression and suicide? You are creating the most hostile of environments for these teens.

Yes, there are pressures we didn’t experience as kids that you do experience. Schools are shooting ranges and we didn’t experience that. (While my high school experienced a few bomb threats that caused evacuations, we never trained what to do in the event of a mass shooter, and I cannot even imagine doing that.) But if our politicians had the will, we could fix that.

But when I was a teen girl, there was pressure to look a certain way, dress a certain way and fit in. And I didn’t do any of those things. I was too skinny, flat chested, with frizzy black hair and a style that read, “You aren’t from here, are you?” I was called “freak” regularly, got into at least one fight, was touched inappropriately in the hall more times than I can count, and hated every morning when the clock hit 7 a.m.

When senior year rolled around, I had completed enough credits to start leaving campus early for work in the afternoons. It was the best thing that ever happened to me — until my male boss made me feel uncomfortable in the office. Every evening, sitting in my powder blue Plymouth Horizon in traffic on the freeway, I’d think, “I could keep driving north to Canada, cross the border and never look back.”

So no, my young friends, I don’t know where all this shock from adults is coming from because we went through much of this too. Worse, no one is telling you what they’ll do to fix it. You deserve better. And I’m sorry.

Now back to the adults reading this: Put yourself in your way-back machine — but leave your rose-colored glasses at home — and remember your junior high and high school experience. Now, come back to today and take a long hard look at what these teens are telling you. Sound familiar? It’s about time we did something to fix what we went through back then and what the teens are going through now, don’t you think?

And maybe it could start with something no adult ever did for us when we were young. Let’s start by asking the teens, “How can we help?” And then actually following up on it.