The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the bivalent COVID booster shots Wedensday – a reformulation split between the orginal mRNA vaccine formula and an updated version targeted to the most recent Omicron variants.

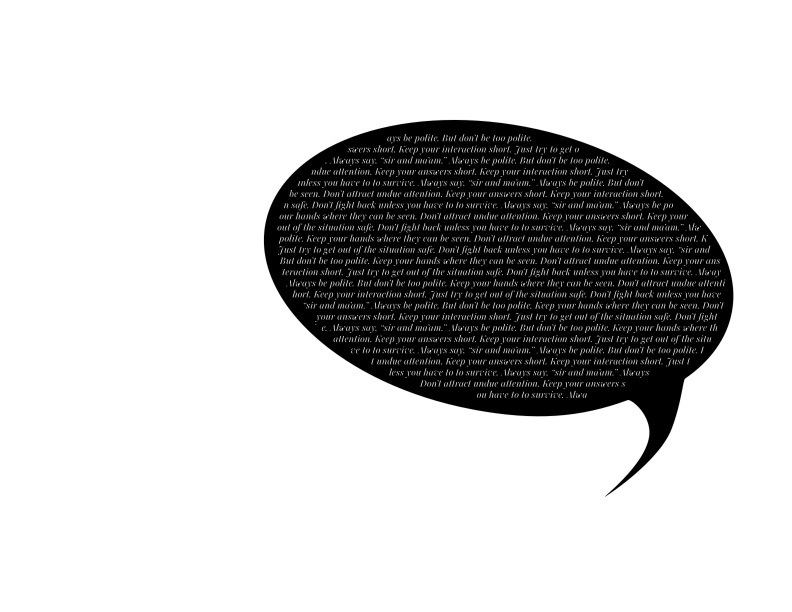

It’s a formulation long overdue. Afterall, Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 swept the world this summer. But it’s a formulation that offers no gauruntees since we don’t know what variant will come next; if it will be in the Omicron line or if it will escape the immunity provided by this booster; the previous vaccines and by previous infections. And that’s why I will continue to wear a good fitting mask that provides fine particle filtration such as an N95 or similar.

I won’t go so far as I did the first two and a half years of this pandemic. You see, I sat out the beginning of COVID as a reporter. In fact, I also sat out most of 2020, 2021 and 2022 from society.

I tend to get sick easily, and despite my strong belief in vaccinations, I don’t have a very good history of seroconversion. It often takes multiple boosters or full repetition of vaccine series for my body to show immunity from a vaccine.

My household took extreme cautions early in 2020 to protect me: good masking beginning in March 2020, isolating me as much as possible, etc.

In the last couple of years, we learned that while my risk for catching COVID isn’t necessarily higher because of my diagnosed disease, Ehlers Danlos, or its associated complications, I am at a higher risk of complications from COVID because of some of my complications such as multi-valvular regurgitation and aortic insufficiency; heritable thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection (hTAAD); and gastroparesis and micro-deficiencies. Additionally, if I did catch COVID, I am not eligible for the drug Paxlovid due to a drug interaction with my cardiac medications.

My partner and I finally caught COVID in the first days of June 2022. We don’t know where we caught it. It could have been one of several appointments where I was the only masked person in the waiting room. It could have been one of his side gigs where he took off his mask to drink something.

The first day of symptoms I excused as just having an bad day; EDS and its complications can leave me feeling drained sometimes, and joint pains are common.

The second morning, I lost my voice. Vocal cord troubles are something that comes anytime I have a terrible upper respiratory infection. (Remember: connective tissues are everywhere, and if something such as a respiratory infection irritates or inflames my connective tissues such as those involve in my vocal cords, my voice is sure to be affected. I took a rapid antigen test (RAT), and it immediately turned positive. I woke up my partner who also took a RAT and got a positive result.

I phoned my internal medicine doctor, who said he’d need a few hours to figure out exactly how to get me some treatment; in the meantime, if any of my vital signs or symptoms worsened, I needed to get to the emergency room.

By 10 a.m. that day, despite my heart meds, my heart was racing and my blood pressure was sinking. My pain level was rising, and my chest hurt from my rising heart rate. My partner and I knew it was time to take me to the hospital. I grabbed my rapid test and my iPad (to work as my voice) and he drove me to hospital, where he dropped me off at the ER entrance at 11 a.m. not knowing when he would see me again.

When I made it to the nurse check-in desk, I showed my positive RAT, motioned to my chest to indicate chest pain and to my throat and mouth to indicate that I had lost my voice. She checked me in and led me back to a crowded triage area. I was called back, and showed the triage nurse a short SBAR — an old nursing acronym for situation, background, assessment and recommendation — that I had typed up about myself. The nurse took my vital signs, and I was sent for some blood work and an ECG. Then, I was told to go wait in a crowded, mostly unmasked waiting room. I pulled my mask tighter, not wanting to infect anyone.

As I waited hour after hour, my phone would occasionally ring: a nurse checking on me, letting me know they couldn’t have direct contact with me since I had an airborne infection; registration checking me in via phone from a room 10 feet away where they were checking in the other patients, apologizing because of “airborne precautions.” But there I sat, in the packed waiting room, where some patients were forced to stand while they waited.

As I waited, my headache grew worse, and my joints grew to a level of pain I had only felt once before – years earlier when I had been infected with H1N1. I began to wonder if I was finally feverish. I walked up to the front desk and asked the check-in nurse for acetaminophen. She called me a few minutes later and passed a medicine cup and small cup of water through the opening in the glass.

Sometime around 9 p.m., I was finally called back; an isolation room was ready for me. I showed the nurse, followed by the resident, then the attending my SBAR, and offered to type up answers as it was becoming extremely painful for me to try to use my raspy whisper of a voice. The resident asked me if I was certain I had COVID and not streptococcus. I showed the positive COVID RAT and used my remaining voice to explain that I’d had strep throat so many times — four times in a single year once — that I could assure her this was not strep simply by the way it felt. Still, she was unconvinced. She wanted to order a strep test.

Instead, they ordered another RAT and then asked me more about my current conditions. I carefully — my remaining voice barely audible — explained EDS, the cardiac complications and that ivabradine is contraindicated with Paxlovid. I said that my chest hurt and that this happens when my heart races for long periods of time, and I am on ivabradine to try to control inappropriate sinus tachycardia. I suggested that perhaps she or the attended consult with my congenital cardiologist or EDS specialist, either of whom would be happy to help in this situation. I said even my internal medicine doctor would not mind a page at this hour if it meant I get good care. I was told they didn’t need to page anyone because they are the ER.

Finally, after much discussion between the attending and the resident, a course of monoclonal antibodies (MAB) was chosen.

Shortly after midnight, after the shift-change for the doctors, I was given the MAB injections. “You’ll feel better in 3 days or so,” the nurse told me.

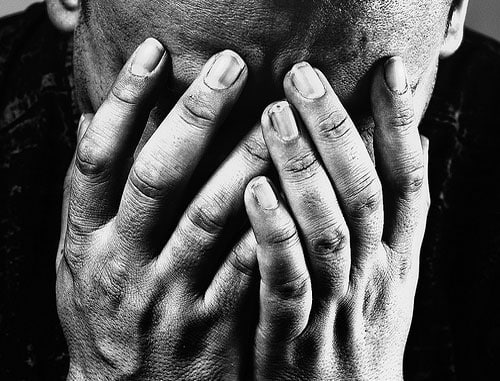

By this time, I was in so much pain, I could not sit still on the gurney. I had to pace and move around simply to keep from my joints freezing. The nurse re-checked my blood pressure, heart rate, pulse ox and around 3 a.m., I was released to go home.

When I returned home, I rechecked all my vitals, including my temperature: 103.9. I had already maxed out my acetaminophen for the day, so I cooled myself with a cold shower.

That’s the last thing I remember for about a week.

My partner recalls that there was much of the week where I was so sick that he thought I was dying, but he didn’t want to take me back to the ER because they had released me with a high temp, they didn’t know what to do with me when I was there, and he knew that per my wishes if I was going to die, it sure as hell wasn’t going to be in a hospital without him by my side.

For the first couple of days, he said I didn’t get out of bed at all. For the days after, I only got out of bed for broth. After that, I began trying to be out of bed more, but he tells me, I wasn’t very present.

My memory starts back in the second week of COVID. My partner was on the mend by this point and back to exercising. I was trying to get out by helping him walk the dogs around the block, but it was slow going. Things beyond that are a little spotty.

By the third week, my mind was active, but my body was a little sluggish. My brain was ready and raring to go, but I was still coughing, aching and tired. I was frustrated. My partner told me that I had told him, “As long as I don’t die, end up on a ventilator or get long COVID, the monoclonal antibodies did their jobs.” I don’t remember saying that but I’m fairly smart, so I can believe I said it.

I’m happy to say I survived COVID, and it seems that I have no long-term consequences. But I fear for another infection.

So while I don’t know how protective the new booster will be against any future infection, I do know I will get it because I’m taking the chance that it will help. But I’ll also be wearing a high quality good-fitting mask because I don’t want to struggle to survive COVID again.