We can save the small-town newspaper

Every time a hometown paper dies, a little piece of me dies too.

Perhaps that sounds a little melodramatic, but I cut my journalistic teeth at small town papers where high school sports can hold up a Friday night deadline, and subscribers read about their family, friends and neighbors.

My first college internship was at the Jackson Citizen Patriot in Jackson, Mich. To the locals, the Cit Pat, a local family-owned paper back then, ended the day like the sunset. You could count on a Cit Pat reporter to be at every Jackson event, whether it be the Hot Air Balloon Jubilee or the Jackson County Fair. Of course we covered the state penitentiary, which sat just north of downtown, the city government and the hospitals, which at the time numbered two to serve what was then a town of more than 36,000 and a county of more than 158,000. The Cit Pat building was at the southwest end of downtown in a beautiful two-story stone building, with the newsroom on the second floor. I don’t know if it’s still there. What I do knows is that now the Cit Pat is owned by MLive, a conglomerate of local Michigan papers owned by Advance Local, which is owned by Advance (owner of Condé Nast and a major shareholder in Charter Communications, Warner Bros. Discovery and Reddit).

My second internship was at the Bloomington (Ind.) Herald-Times. The H-T took on a shaved-headed college student reporter who had just left college with only a semester to go for a myriad of reasons but was certain she wanted to continue to pursue a career in journalism. That college student was me. In that semester-long features internship, I had the opportunity to join an all-hands-on-deck coverage of an Indiana University campus riot and do a piece that required me to make international calls to a local man who was recently detained in the West Bank for protesting Israeli settlement expansion. At the time, the newspaper was owned by the small communications company Schurz Communication, which started in the latter half of the 1800s with another Indiana paper, the South Bend Tribune. I’d love to tell you Schurz still owns both papers – or at least one of them – but it doesn’t. Somewhere along the way, as Gatehouse and Gannett swallowed up paper after paper, until they merged in 2020, both the H-T and the South Bend Tribune came under Gennett ownership.

In 2004, I landed at the Monroe (Mich.) Evening News as health editor and reporter. I pushed for the four-page health section to be filled by news written in-house instead of pulled from the wire and revamped the monthly section for children, Your Health for Kids. But after a year at the EEOC, the business side of the Monroe Publishing Company no longer saw the need for a health editor to oversee the section. I was offered the open role at the company’s weekly free paper that covered the community of Bedford Township, a growing suburb of Toledo, Ohio. I saw it as a way to step up to larger market media in the future. I unfortunately was running headlong into the Great Recession. Now, The Monroe News is owned by Gannett and runs on a skeleton staff, and Bedford Now is no longer published.

The recent round of layoffs at papers by Gannett, emptying out newsrooms, reignited an idea I’ve been mulling over for a long time: a nationwide network of individual newspapers in each community that works on donations. Think of it as your local public radio station but as a newspaper – or news site since most of us read our newspaper on a screen these days. I call it a “public newspaper.”

The first time I started to think about the concept of a “public newspaper,” I was sitting at a media professionals conference in Seattle.

It was 1998, I think. Maybe 1999. We were in a hotel downtown, maybe a 20-minute walk from the famed Public Market, discussing how the internet would change the future of journalism. Some said it would be the death of the newspaper industry while others said it would bring a resurgence of long-form journalism to newspapers both local and national.

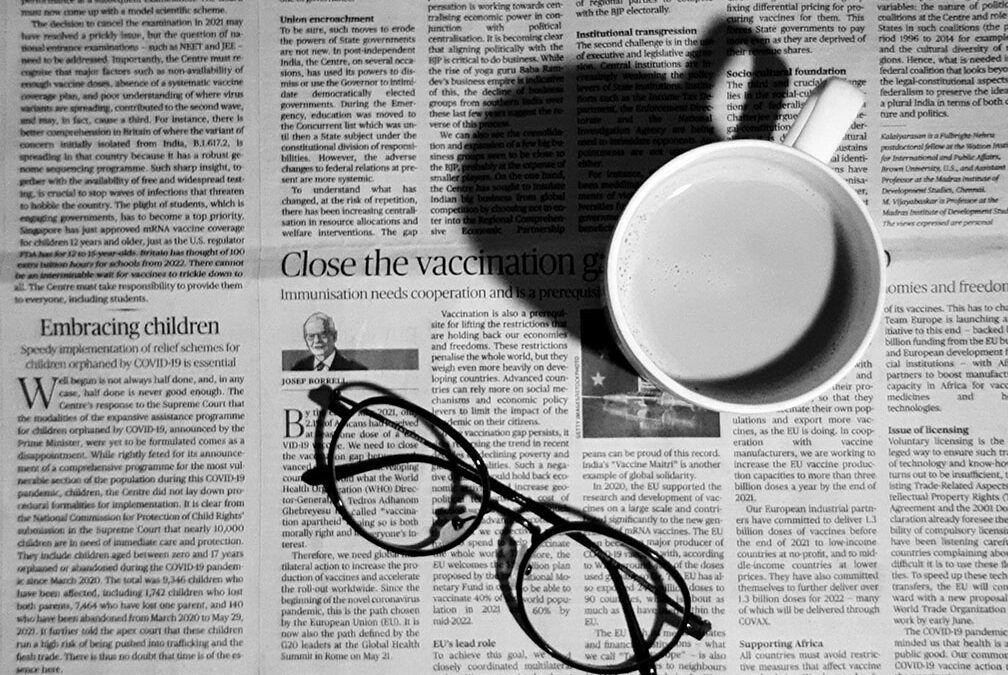

I don’t think anyone had their eye on a nearly two decade-long slump that included venture capitalism firms buying up whatever small-town papers in the Midwest Gannett and Gatehouse Media didn’t buy first, followed by a merger that was used as an excuse for more newsroom cutbacks. No one discussed things like paywalls; declining readership and subscription rates; personals, sales and wanted ads moving to Craigslist; or ad buys dropping significantly and having a whole new rate model on the web.

As I listened to older, wiser editors and reporters conjure the future in their cracked crystal balls, I thought to myself, what if newspapers worked on the same model as public radio: a network of local news radio programing or stations that feed a national news organization, National Public Radio, that then provides national news programing in return – and the whole network works on donations?

Throughout my career as a reporter, as I’ve seen slight ups, big downs and what sometimes seems like the bottom falling out, the idea keeps coming back to me.

Local newspapers are the backbones of communities, and for too long we have seen them bought and sold, downsized then decimated. Every village and hamlet and town and small city should have a local newspaper with a newsroom of reporters who know the local business, the local principals, the local school board members, and the local city council members as well as the know the town elders who have regular seats at the diner and the parents at the playground. Every town has news, and every town needs someone to cover it, whether it’s the Friday night high school basketball game or the town parade.

Trust in our media comes from our local media. The better the local coverage and the more the reporters get to know the community, the more the community trusts the news.

Now imagine all these tiny towns, with their daily or semi-weekly papers, contribute to each other and national reporters contribute to the entire network of local papers. The best part? All the papers are free. You can choose to donate if you like, but you don’t have to pay.

Today, most people read their newspapers on an app or on the web site rather on the newsprint. The Washington Post has an app. The New York Times has an app. The Wall Street Journal has an app. Many newspapers have an app. Even NPR and many local public radio stations have an app for listening, reading, merchandise and more. This would be the way to deliver not only a newspaper in 2022, but also a nationwide network of newspapers – and additionally could be a great way to ask for donations a couple times a year.

Of course, I say all of this with the realization that I know very little about how a donation-driven news service such as public radio actually works as a business. My degrees are in the areas of health and science, not finance, business or management. I can manage a health section and a handful of reporters, but I certainly know (to use a colloquialism) bunk all about running a national network of news sites that run on donations, or about collecting donations to run those news sites for that matter. Heck, I don’t even know how to build a news site.

What I do know is that of all the papers I interned or worked for full-time, only two are not currently owned by Gannett and even those are running on a skeleton staff at barely the quality of reporting they once did.

Journalism won’t be saved by “citizen journalists,” by venture capitalists buying out small papers and destroying them, or by less news from fewer reporters. Journalism and trust in journalism will only be saved by more professional, well done, strong local news in every town.